“I can’t believe I went up 12 points on the ACT! Cannot believe it. Crying with happiness. Wow!”

After 20 years of helping students grow their ACT and SAT scores, finding an email like this at the top of my inbox still brings me the greatest joy. More satisfying still is that this email came from a student with diagnosed learning disabilities, one who worked hard to develop critical reading and reasoning skills, applied for and earned extended-time accommodations, and was ultimately able to deliver that “show what you know” performance.

Learning-disabled students—when given appropriate accommodations and instruction—are capable of remarkable growth. What’s more, it appears to be, in part, a matter of time: ACT and SAT accommodations, such as extended time, can make that critical difference for these students.

ACT and SAT accommodations – what are they?

ACT and SAT accommodations are provided by ACT and the College Board (SAT)—as well as primary, secondary, and postsecondary institutions—to test takers with disabilities or health-related needs. ACT and SAT accommodations can range from extended-time to multiple-day testing to computer testing for essays to extra breaks for medication or snacks to a host of other concessions.

These accommodations are not designed to remove standardization, because that would undermine the validity of the test, but rather to make appropriate adjustments, given a student’s disabling conditions, that will provide an equal opportunity to demonstrate skills and knowledge.

Join the A+ Newsletter!

We promise, no spam—just a monthly dose of educational insight, strategies, and exclusive tips straight to your inbox.

In other words, ACT and SAT accommodations are designed to give disabled students a fair chance to “show what they know.”

Who qualifies for ACT and SAT accommodations?

The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 and federal regulations under Section 504 extended civil rights protections to disabled people. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 required test publishers and administrators to provide reasonable accommodations for disabling conditions (Asquith and Feld, 1992).

The disabilities that receive accommodations most frequently are learning disabilities, including dyslexia, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and other specific mental disorders. While the range of learning disabilities in their variable combinations may require multiple accommodations, extended time is a frequent accommodation for students with learning disabilities.

Extended time can provide a student with a visual sequencing disturbance more time to properly see letters and numbers, or a student with dyslexia the necessary time to read a test more slowly and comprehend more accurately.

What steps do parents or guardians need to take in order for their child to receive ACT or SAT accommodations?

Step 1: Determine Eligibility

Eligibility for SAT accommodations requires that the disability must result in a relevant functional limitation. For ACT accommodations, the disability must substantially limit a major life activity compared to the average person in the general population. The longer the case has been documented, the more persuasive. The more the student relies on the specific accommodations in school, i.e., uses the accommodations for in-school testing because they are truly needed, the more compelling.

Step 2: Gather Necessary Documentation

Provide documentation that states the specific diagnosis, as captured in the student’s IEP, 504 Plan, or neuropsychological or psychoeducational testing. Make sure that:

- The documentation is current (diagnosed or reconfirmed within the past 3 years).

- The documentation describes substantial limitations (adverse effects on learning or other major life activities) resulting from impairment, as stated by test results.

- The documentation establishes the professional credentials of the evaluators.

- The diagnosis is supported with comprehensive assessments (neuropsychological or psychoeducational evaluations) with evaluation data used to arrive at diagnosis.

Step 3: Submit

Work with learning resources counselors at your school to submit to each test agency. Your school must support and facilitate the application for ACT or SAT accommodations.

Step 4: Accept or Appeal

If granted the desired conditions, respond and accept. If denied, a rationale will be provided, specifying what further documentation is required for your student to receive ACT or SAT accommodations. Appeal with further documentation: additional letters from teachers, evaluators, or further testing may be required to satisfy the review committee.

Continued advocacy is sometimes necessary and often very successful. If the student’s educational needs are clear and justifiable, fight for the necessary ACT and SAT accommodations—it’s the student’s right to a fair test administration.

Timing & the future of tests

There is a national trend in standardized testing towards universally designed assessments that lessen the impact of timing as a variable that impacts test performance. Assessments like PARCC exam relax time significantly, and the Smarter Balance state-wide assessment is not timed at all; these exams are aiming to capture academic readiness while disaggregating the extraneous variable of time. Even SAT in its 2016 revision is reflecting this trend.

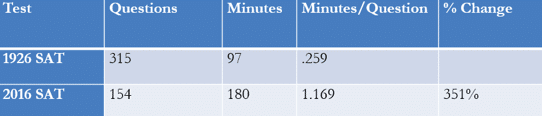

One index to its transformation is in the matter of time: the original SAT from 1926 featured 315 questions with a time limit of 97 minutes. The 2016 SAT features 154 questions in 180 minutes.

What is the significance of that construct change?

Students now have 351% more time per question than they did in 1926. That 90-year evolution of the test reflects an important shift from a speeded IQ exam to a less speeded academic growth and readiness instrument. That’s a movement in the right direction—in the direction of minimizing timing as something the test assesses and instead allowing students to “show what they know” on important measures of academic readiness.

Timing & the future of individualized instruction

For those of us who work closely with students on personalized learning, we know that one size does not fit all, and a movement in education is evolving to support the science around our knowledge and experience.

Todd Rose, Director of The Mind, Brain, and Education Program at Harvard School of Education, focuses his research on individuality and personalization. Rose’s book The End of Average is a persuasive review of research that proves there is no such thing as average body size, average talent, average intelligence, or average character—or average brains, for that matter. Our modern conception of the average person is a misconception.

As an alternative to the average, Rose proposes a science of the individual, focusing on individualized pathways for learning that differ in the time and sequence required to learn. We tend to view learning and development as a ladder—you differ by speed. We tend to think fast equals smart. Someone’s a “quick study” or “quick learner.” For Rose, however, pace is not correlated with ability.

And Rose’s insights of course crystallize around standardized tests, which are designed towards average assumptions, especially around the time necessary for completion. The early assumption around timed testing was that if you can’t finish, you’re not smart enough to use extra time anyway.

Rose cites Benjamin Bloom’s work as a primary challenge to this thinking. In the 1970s and 80s, schools and politicians were debating whether schools could narrow the achievement gap, because of issues outside of their control like poverty. Bloom believed it was possible.

Bloom hypothesized that differences in capacity to learn resulted from artificial constraints like curriculum planners determining the pace and timing of learning and testing.

He organized a study of students following a “fixed-pace group” protocol versus those who were “self-paced with a tutor.” The results show that without time constraint, the lowest performer under time constraint completes the work with the highest level of performance when provided more time and focused tutoring.

Bloom’s study shows that equating learning speed or performance speed with learning ability is irrefutably wrong. If you give a little flexibility, you unlock talent.

What does this mean then for students with learning disabilities that impair their speeded performance? It means that when you constrain their time, you constrain their talent.

Test-taking Performance

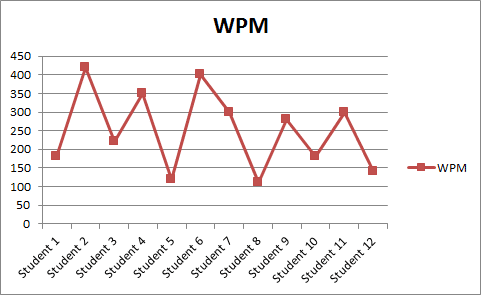

Bloom’s research resonates with my own experiences tutoring students for higher test performance on the ACT and SAT. For example, I always calculate my students’ word-per-minute (WPM) reading rates, which tend to range anywhere from 100 to 600 words per minute.

This range represents a profound difference in WPM reading rates, especially when you extrapolate what this means for these students in terms of their individual experience of pacing through homework, timed tests, etc. I’ve worked with students in the same school, who sit next to each other in class, engaging the same material, but with a dramatic 6X differential between their WPM reading rates. And this significant differential is almost always unknown to them and often to their teachers as well.

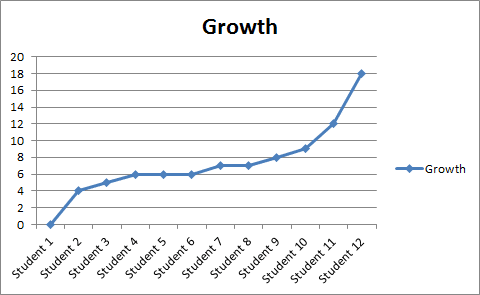

I look at WPM reading rates in relation to students’ ACT or SAT growth (from diagnostic to official test) as well as in relation to the factor of extended-time ACT and SAT accommodations.

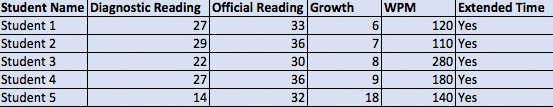

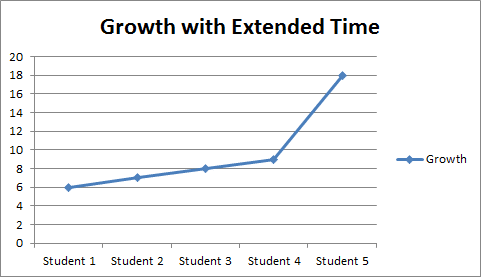

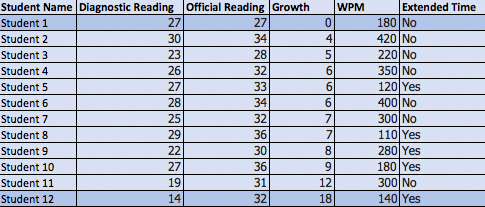

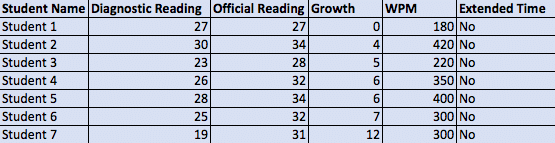

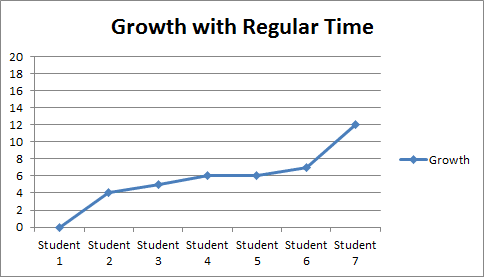

A small sample set of ACT Reading students are listed below with these factors identified:

In fact, the student in this data set with one of the slower WPM reading rates (140 WPM) displays the greatest growth. Why? Interestingly, these students’ WPM reading rates are not correlated to their ultimate ACT reading growth as the detail below indicates.

The difference of extended-time testing is an important variable. The combination of some exceptionally hard work, targeted skill building, AND a multiple-day, extended-time administration allowed this student to post 18 points of reading growth on ACT Reading.

Overall, extended-time students using ACT or SAT accommodations demonstrate the greater growth compared to students with regular time. This trend continues in larger sets of students, but this quick snapshot is telling.

Given my own instructional experience, I of course agree with Bloom and Rose: when you constrain time, you also constrain talent. When you offer flexibility around timing with ACT or SAT accommodations to the capable but functionally disabled student, you can unlock great potential.

——————-

Shinn, E. & Ofiesh, N. (2012). Cognitive Diversity and Implications for Test Design. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability. 25 (3), pp. 227-245.

Ofiesh, N. & Bisagno, J. (2009). Test validity and test accommodations. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, (15) 3.

Ofiesh, N. (2009). Students with LD and high stakes testing. Learning Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, (15) 3.